Borges was eager to see the faces of his first hundred readers. My eagerness is different. Are we all standing before a challenge to see the faces of the last hundred of readers, or, to be less pathetic, the faces of the last hundred readers of the novel?

Answering to that, let us put the question when and where, in which part of the text the reading of a novel starts and when and where the reading of a novel ends. How is the beginning and the end of a novel, the beginning and the end of reading, conditioned by what Jasmina Mihajlovic calls: reading and sex? Must the novel have an end? And what in fact is the end of a novel, of a literary work? And is it unavoidably only one? How many ends can a novel or a theatre play have?

To those questions I have found some answers while writing my books. Long ago I came to understand that the arts are “reversible” and “non-reversible”. There are some arts which enable the recipient to approach the work from various sides, or even to go around it and have a good look at it changing the spot, the perspective and the direction of his looking at it according to his own preference, as is the case with architecture, sculpture or painting, that are reversible. Other non-reversible arts, such as music and literature look like one-way roads on which everything moves from the beginning to the end, from birth to death. I have always wished to make literature, which is non reversible art, a reversible one. Therefore my novels have no beginning and no end in the classical meaning of the word.

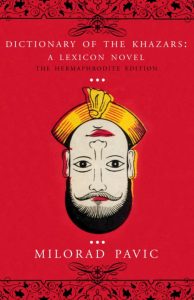

For instance, Dictionary of the Khazars is “a lexicon novel in 100,000 words”, and according to the alphabet of various languages, the novel ends differently. The original version of Dictionary of the Khazars, printed in the Cyrillic alphabet, ends with a Latin quotation: ” sed venit ut illa impleam et confirmem, Mattheus”. My novel in Greek translation ends with a sentence: “I have immediately noticed that there are three fears in me, and not one”. The English, Jewish, Spanish, and Danish version of Dictionary of the Khazars end in this way: “Then, when the reader returned, the entire process would be reversed, and Tibbon would correct the translation on the basis of the impressions he had derived from this reading walk”. The Serbian version printed in the Latin alphabet, the Swedish version published at Nordsteds, the Holland version, the Czech version and the German version , end with the following sentence: “That look wrote Koen’s name in the air, lighted the wick, and lit up her way to the house”. The Hungarian version of Dictionary of the Khazars ends with sentence: “He simply wanted to draw your attention to what your nature is like”. The Italian and Catalonian versions end in this way: “Indeed the Chazar jar serves to this day, although it has long since ceased to exist.” The Japanese version, published by “Tokyo Zogen Sha” ends with the sentence: “The girl had given birth to a fast quick daughter – her death; in that death her beauty had been divided on whey and curdled milk, and at the bottom a mouth was seen keeping the root of reeds”.

My second novel, Landscape Painted with Tea (comparable with cross-word puzzles) brings the portraits of the book’s characters into the first plan if read vertically. If the same chapters are read horizontally (in the “classical way”), they put into the first plan the plot of the novel and its development. Let us discuss the beginning and the end of the novel in this case as well. First of all, this novel ends in one way if it is read by a woman-reader, and in another way if the reader is a man. Of course, the beginnings and the ends of this novel differ from each other depending as well on the fact that the novel is read vertically or horizontally. Landscape Painted with Tea, if read horizontally, has the next beginning: “No undelivered slap should ever be taken to the grave”. For those who wish to read the same way – across, this novel ends with the sentence: “The reader will not be so stupid not to remember what happened to Atanasije Svilar, whose name, for some time, used to be Razin”. Landscape Painted with Tea if read vertically, begins with the sentence: “In preparing this Testimonial to our friend, schoolmate, and benefactor, architect Atanas Fyodorovich Razin, alias Atanas Svilar, who once inscribed his name with his tongue on the backs of the most beautiful women of our generation…” The same way read this novel ends with the sentence: “I ran into the church”.

After the novel-dictionary and the novel-crossword puzzle I tried again to transfer the novel into the row of the reversible arts. It is The Inner Side of the Wind. A klepsydra – novel. It has two front pages and it is best to read it one and a half times, as the famous archaeologist, Dragoslav Srejovic, once said. The end is in the middle, where the lovers of this mythical tale, Hero and Leander meet. If you start reading from Leander’s side, the beginning of the novel will be: “All futures have one great virtue: they never look the way you imagine them…” On that side of the book end of the novel will be the following: “It was five minutes past twelve when the towers in a horrible explosion fled into the air taking with them the flames in which Leander’s body had perished”. If you read The Inner Side of the Wind from Hero’s side, the beginning of the book will be: “In the first part of the life, a woman gives birth, and in the second, she kills and buries either herself, or those around her”. If you start reading from that, Hero’s side, the end of the novel will be like this: “According to the bewildered lieutenant it was not till the third day in the evening that Hero’s head yelled in a terrible and deep voice as if it were a man’s”.

My most recent book, Last Love in Constantinople is, in fact, a tarot-novel consisting of 22 chapters corresponding to the cards of the Major Arcana. As it is known, with the help of the tarot, it is possible to foretell the future, and the novel Last Love in Constantinople has several keys as the cards themselves. In other words this novel is a direction for tarot fortune-telling and can be “used” in more different ways. But the novel is not foretelling future to it’s heroes, but to it’s readers. It is possible to read-in the meaning of the tarot cards into the chapters of the novel (that bear the same appellations and numbers as the individual cards). It is possible to read-in the sense of the chapters of the novel into the meaning of the cards during fortune-telling. The novel can be used regardless the cards. Also, according to the directions for the tarot, that are given in the content, you can first of all throw the cards, and then read the chapters in the way cards fell on the table.

Therefore we can conclude that from the described novels we can come out not only through one exit, but also through more ways out that are far from each other.

Slowly I lose from my sight the difference between the house and the book, and this is, perhaps, the most important thing I have to say in this text. But let us turn to the more general question, often raised in these days. Is the end of the novel approaching? Is the end of the novel before us or already behind us, ask those people that are followers of the thought that we are already living in the post history times. Is it also a post romanesque time? Have we passed through the finish without even noticing, and now all of us are running together in an already finished race? I believe it cannot be said so, unless we are struck by some nuclear cataclysm of cosmic proportions. I am more inclined to say that we are rather at the termination of one manner of reading. It is the crisis of our way of reading the novel, and not the novel itself. The novel – one-way road is in a crisis. Something else is in a crisis as well. It is the graphic sight of the novel. This is to say: the book is in a crisis. Hyperfiction is teaching us a novel can move as our mind moves, in all directions at once. And to be interactive.

I tried to change the way of the reading increasing the role and responsibility of the reader in the process of creating a novel (let us not forget that in the world there are much more talented readers than talented authors and literary critics). I have left to them, to the readers, the decision about the choice of the plots and the development of the situations in the novel: where the reading will begin, and where it will end, even the decision about the destiny of the main characters. But in order to change the way of reading, I had to change the way of writing. Therefore these lines should not be understood exclusively as a talk about the form of the novel. This is at the same time both a talk of its content. In fact, the content of any novel has been, so to say, on Procrust’s bed for two thousand years always subjected to the merciless model of form. I believe that an end has come to this. Each novel should select its specific form, each story can search for, and find, its adequate body… Computer is teaching us it is possible. But if you do not like computers, have a look what architecture is teaching us.

Architecture changes our way of life. A literary work, if we consider it as a house, can change our way of life. A novel can be a home as well. At least for a while.

(Copyright : Jasmina Mihajlovic. Published with permission)

About the author:

Milorad Pavić, the erudite Serbian writer, university professor, literary historian, and member of the Serbian Academy of Science and Arts (1991-2009), was born on 15 October 1929 in Belgrade. As fiction writer, he was virtually unknown until 1984 when “Dictionary of the Khazars: A Lexicon Novel in 100,000 Words” brought him an instant worldwide fame. His works have been translated in more than 40 languages and are now published all over the world. When it comes to unconventional novel structures and experiments with form, Milorad Pavic is the first name that comes to mind with his meticulously executed and intricately twisted labyrinths of the imagination – his “metanovels”.

He was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature multiple times. Jasmina Mihajlović, Pavić’s main biographer, bibliographer, and editor of his collected works currently manages “The Milorad Pavić Bequest”.