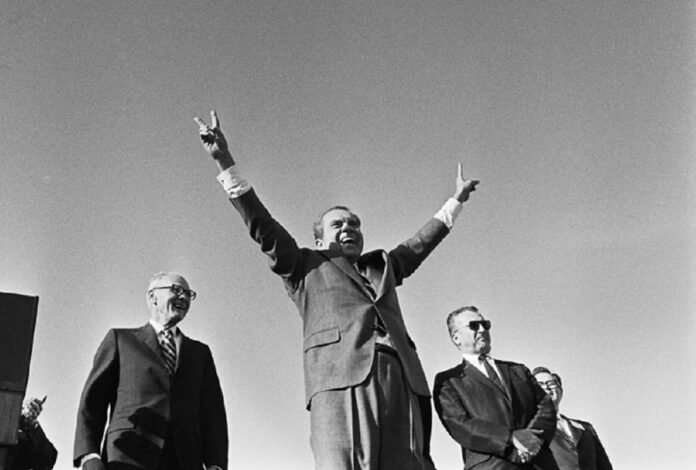

Richard Nixon’s life was full of Pats. First came his wife Pat. Next, Pat Hitt. She was the national co‑chair of his 1968 presidential race and then Assistant Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare. Third was Pat Hillings, Nixon’s successor in the House of Representatives and later a campaign adviser. Then Pat Buchanan, the first person Nixon’s presidential campaign hired to perform opposition research, write partisan speeches, travel with the candidate, and ultimately become a right-wing columnist. Number five, Pat Palangi, head of Nixon’s message bureau at the 1968 Republican National Convention—until he disappeared, destination unknown. I replaced him.

And finally, an intern: Pat Smith Nagy. She’s the one I want to tell you about.

*

We met in 1968, when she worked for the Republican National Committee and I for Nixon’s presidential campaign. We were both college kids. The daughter of Eleanor Smith, one of Pat Hitt’s chief assistants, Pat Smith Nagy was the archetype of the California girl. Bright, bubbly, and blond. A native and a surfer. My age. Idealistic like me. Matching goals in politics. But romance was out of the question; no chemistry. Still, the banter flew nonstop between us—gossip about senators, thoughts on election strategy, notes on policy. I never tired of her throaty voice, a little too loud, and her Southern California-isms like “bitchen” and “groovy.”

In November 1968 we celebrated Nixon’s victory together. Four days after the election, I returned to college while Pat stayed on, helping fill jobs in the new administration. She displayed foresight. In an early December 1968 letter to me, she wrote, “Cross your fingers hard that John Mitchell doesn’t get anything, or we may be headed for real trouble.” We didn’t cross our fingers hard enough. Mitchell became attorney general and eventually, for nineteen months, a federal prisoner.

In 1969, while I suffered through my first year of law school, Pat zipped up the political ziggurat. She joined George Murphy’s California campaign for the U.S. Senate, graduated from UCLA, and returned to Washington to work at the Department of the Interior.

“Bummer,” Pat said over the phone after I complained about reading too many boring cases on contracts. She couldn’t talk long; she had a meeting on Capitol Hill.

Pat’s mother sensed that my mood was drifting downhill. Eleanor wanted to help but could do little while I remained in law school. In January 1970 a letter arrived from her saying, “You young people have to stay in there and keep pitching. I know it’s very easy to get disillusioned, but if we all skipped out, there would be nobody but what I call dodo birds running the show, and where does that leave us? So you all have just got to save the country.” Pat took her mother’s advice. I didn’t and every night, after slamming shut my casebooks, I regretted not doing so.

A golden chance to dip into public life arrived in 1971, during my second year of law school. Pat was helping organize the White House Conference on Youth, a once-a-decade event. For her the project was ideal: gather one thousand young delegates from every state—college kids, young housewives, boys in the military, working youths. Every race and creed. Also bring in about four hundred adult delegates.

“I’ll lobby for you,” she said. “Send me a resume.”

*

It looked so official, what arrived in that creamy white envelope: The President invites you to attend the meetings of the White House Conference on Youth. And above those magic words, the Great Seal of the United States. At twenty-four I’d just made the cut; the conference defined “youths” as between fourteen and twenty-four. The organizers split us delegates into ten task forces. Pat landed on the environment panel; so did her sister Judy, who was seventeen. They slotted me into the task force on legal rights and justice. Our jobs: formulate recommendations for the federal agencies. The week before the conference, I stopped going out at night for fear of catching a cold and missing the event.

Ostensibly to avoid demonstrations against the Vietnam War, they flew us delegates to Denver and bused us to the YMCA of the Rockies, 7,500 feet above sea level, near Estes Park, Colorado. Rocky Mountain National Park surrounded us on three sides. There was irony in the venue. Arriving on a day of low clouds and high humidity, one delegate surveyed the terrain, turned to me, and said, “This place bears a close resemblance to Dienbienphu.”

The Vietnam likeness ended there. The orientation materials told us to prepare for “spring-like weather.” Spring indeed. Starting on day two, it snowed and grew so cold that the Army had to truck in parkas to protect the delegates, most of whom had not brought proper clothing. The more paranoid among us hollered—I kid you not—that we were being drafted. Not Pat. Wrapped in her parka with “US Army” emblazoned on the front, she acted so enthusiastic that I wouldn’t have been surprised if she’d yelled out, “Hooah.”

But her cheer vanished each time Pat and I trooped into the cafeteria for dinner, and she analyzed the salad, the vegetables, and the protein.

“This mystery meat,” she said. “They cooked it too long. Why didn’t they sear it? And it could use garlic.”

A teenage delegate on the other side of the long table where we sat looked at us and wrinkled her nose. “It’s yucky,” she said.

Pat continued, “And the canned corn is soggy. Corn doesn’t go with spinach. I would have picked something unusual.”

We were two decades away from broccolini and kale, yet Pat seemed to be envisioning new choices for the American palate. Years on, waiting on tables and watching Julia Child, Pat would become a foodie. I couldn’t boil an egg; still can’t.

“What’s on your group’s agenda tomorrow?” I asked.

“Lots of proposals,” Pat said. “We’re going to make a difference. You wait and see.”

Ordinarily, I’m the house pessimist but I believed her. In the wooden cabin where my task force gathered, we sat on folding chairs, on couches, on the floor, and we flung ideas nonstop around the room. Methods to improve the nation’s legal system, streamline the courts, provide counsel for all—and in doing so, prove that politics was the art of the everything-is-possible. One woman, a former addict, wanted to require judges to visit every jail and prison where they could sentence defendants. I silently promised that if a governor ever put me on the bench, I’d follow her suggestion.

On our last night, between bites of whatever ended up on our plates, Pat said, “We’ve got some great recommendations. Your group too, right?” She chewed on her dinner. “Ick, this chicken is too tough. Why didn’t they baste it?”

I said something like, “Ours are excellent too.”

Outside the snowfall had eased, with residual flakes tickling my nose and settling in Pat’s hair, there to sparkle. “Meet me for breakfast tomorrow,” I said. That would be Friday, our last day, with time to socialize built into the schedule.

We didn’t meet. Shortly after 6 a.m. on Friday morning, someone barged into the bunk room where I was sleeping.

“Get up,” he shouted. “Snowing bad. We’re evacuating.”

Twenty or so of us stumbled from our bunk beds and let fly with the tirades of the sleep deprived. Along with other groggy delegates, I stuffed my clothes into a suitcase and trudged through the blizzard to the waiting buses. A few minutes later we were grinding our way down the mountains to the Denver airport, where the weather wasn’t severe enough to cancel our flights. I didn’t see Pat on my bus; she’d boarded another. Nor did I see her at the airport. I didn’t see her again for years.

*

Back at law school the White House Conference receded into dreamy memory, smothered by casebooks full of “hereinabove’s,” “provided, however’s,” and bloated statutes like the Internal Revenue Code. But following graduation in 1972, I still planned to resume my political persona by joining President Nixon’s reelection committee.

That wouldn’t happen, thanks to Watergate. The scandal convinced even Gordon Strachan, a liaison to Nixon’s reelection committee, to urge America’s young to “stay away” from Washington. I ended up practicing law, exactly what I’d planned not to do. Watergate stripped away my hopes for a political future. Contacts—the phrase campaign aides used for the people you’d worked with and reported to—were the key. Once upon a time I had plenty of them. Now too many wore prison uniforms. No longer did time in the White House add cachet to a resume. As one wag joked on television, the Nixon people no longer talked about four more years; they talked about three to ten. I could relate. I visualized three to ten years deposing doctors and drafting indenture agreements, thoughts that brought me close to tears.

Meanwhile Eleanor, Pat’s mother, spent the reelection campaign working as an “executive assistant” at the Republican National Committee. She had nothing to do with the scandal, but still it scarred her and, indirectly, Pat. Watergate touched more than its convicted felons. Said Pat’s younger sister years later, “Looking back, it must have been a devastating time for her. [Eleanor] continued to work for the RNC for another year until she broke down and realized she needed a change. I am sure the pressure after Watergate must have been intense.” Eleanor left the National Committee, moved home to California’s Palm Springs area, met a good man, and married him.

Unlike Eleanor, I did look back. I missed politics, especially national campaigns. Little local races offered scant satisfaction; they couldn’t compare to the thrill of electing the President of the United States. Eleanor was right when she said that in nationwide races, “They threw you in and kept you going.” As Watergate receded into the offing, I couldn’t find a way back in. I pinged Ronald Reagan’s transition team with resumes, then George H.W. Bush’s people in 1988. No reply. My credentials must have languished in slush piles with thousands of other letters from frustrated lawyers.

*

It was 1990 or 1991, late spring. My then girlfriend and I were spending a weekend in the desert. I found Eleanor in the phone book and called. I knew she was through with politics but assumed her daughter wasn’t. Maybe Eleanor could help me find Pat, and then maybe Pat could help me restart a political career.

Eleanor appeared regal, at least a decade below her age, lines barely visible on her face, her voice vibrant, posture ramrod straight. She walked me through her capacious townhouse, elegant furniture and white walls everywhere, ideal desert décor.

Sick of “office work,” wanting a job that was “out in the open, interacting with people,” Pat had returned to California, Eleanor said—Hermosa Beach in the South Bay area—and worked as a waitress at the Marriott Hotel near LAX, a job she adored. Then, because she loved the sun, Pat and her husband bought a second home in the desert, where they eventually moved.

“She runs a fast-food restaurant out here,” Eleanor said. She added nothing beyond its name and address, about a thirty-minute drive from Eleanor’s home.

Pat’s Broasted Chicken was tucked into a strip mall on a street off Palm Desert’s main highway. A place where a motorcycle gang might pull in. Or an unshaven man whose wife had kicked him out of their double-wide. Inside were a counter, three or four plastic tables, and chairs. It was close to one o’clock. I thought at least a couple of people would be in there, ordering lunch. I was wrong.

“Wonderful to see you,” Pat said in a hoarse voice.

I wasn’t sure I was looking at Pat. She had bleary eyes. Barrel chest. Skinny bird legs. Hair matted and oily. Surface capillaries everywhere, rendering her complexion red. I knew I was getting older too—hair turning gray, waist turning thick, bags turning big below my blue-green eyes—but my body was not as broken as my former campaign pal. My girlfriend recognized the problem that I wasn’t observant enough to spot: Pat’s appearance showed signs of alcoholism.

We passed through the inevitable small talk, about what I can’t recall. I may have asked her to define “broasted.” I wanted to ask why she’d picked this franchise instead of a KFC. Was Pat’s Broasted Chicken a franchise at all? It’s possible I did ask about that. If so, I don’t remember the answer. I was too eager to talk politics. I brought up our shared experiences—a July evening cruise down the Potomac with Julie and Tricia Nixon, waiting all night for the election returns, collecting data for The Truth Squad, surrogates who dogged the Democratic nominees wherever they went. None of these cues generated much of a response. I pressed on in search of a memory that would resonate with Pat. I tried the Republican National Convention in Miami Beach.

“That was fun,” she said. Then nothing. It became clear that Pat couldn’t help my career. Sadness crept in, along with a sense of loss.

Into the silence my girlfriend suggested we order a chicken.

“Right,” I said. “We’re up for some lunch.”

Pat said, “Let me get it going.”

She slipped behind the counter and into the kitchen. My girlfriend and I picked one of the circular tables and scraped the chairs toward each other. We waited, the only sounds the hiss of a stove burner, the clang of utensils, and distant traffic.

A slovenly man shuffled in, looked about, and left. It was about 1:45. Our chicken was still broasting.

My girlfriend whispered that she was “getting really hungry.”

Skipping lunch would not have been a crisis for me; I needed to lose weight. It was also getting hot. The air-conditioning barely functioned. Five more minutes without chicken, arms akimbo on her narrow waist, my girlfriend whispered, “What’s going on back there?”

“I have no idea.”

“You want to leave if we don’t get it by two?”

If Pat and I had no history, I would have said yes. Instead, I gazed at the napkins on a corner shelf along with a Styrofoam cup full of plastic utensils.

Eventually our lunch arrived but the woman who once panned the cooking in Estes Park had prepared a bird that we needed a hacksaw to eat. We forced it down. Then—even though I was sure it was hopeless—I tried again for a conversation about the halcyon days, this time the White House Conference on Youth.

“Oh, that,” she said.

I didn’t go on. I should have reminded her about what she’d achieved. Pat and her committee had brought together youths ranging from a member of the Fellowship of Christian Athletes to the president of the Junior Young Buddhists. From a U.S. Marine who’d earned three bronze stars for combat in Vietnam to the director of the National Council to Repeal the Draft. From a juvenile court judge to a seventeen-year-old unwed mother who’d spent two years in a Connecticut correctional institution. They’d recruited the nation’s youngest dean of women, the head of Minnesota’s Youth Franchise Coalition, and a recipient of the Columbia University Book Award. Pat’s team had discovered Laura d’Andrea Tyson, a future chair of the Council of Economic Advisers. They’d also found a seventeen-year-old from Tennessee named Oprah Winfrey (assigned to the task force on poverty). And we delegates did our jobs. In an editorial The New York Times praised us for sending to Washington “an eloquent message of concern about the nation’s present course…an anguished call for leadership of courage and hope, rather than of expediency and fear.”

It was clear that Pat’s life had funneled down to a not-so-fast-food joint. She appeared to be decomposing in one of the sunniest segments of the Sunbelt, the epicenter of the Republicans’ campaign strategy.

Many political leaders—from Presidents on down—rhapsodize about a dotage in their garden surrounded by their kids or in a study with their plaques and books. Pat was experiencing a grittier version of such a denouement. I feared the same fate, albeit in a law office. I’d sought her out for support, for advice, and for contacts that could vault me back into public life, but Pat needed help more than I did, a fact that, thanks to my solipsistic concerns, I missed. The truth was neither of us could help the other.

I paid for lunch and wished her luck.

*

This is what Pat’s sister wrote to me, years later: “Who knows why someone starts drinking? [Watergate] certainly dimmed her enthusiasm for participating in politics later in her life. But I am not sure that led her to drink.”

I’m not sure either. What I do know is that the day Pat wrote her December 1968 letter to me, she was hung over. As in, “Please excuse the typing and run-on sentences in this letter. Last night was a sorority Christmas party, and I really tied one on. My mind is a mass of jumbles, and my coordination is not exactly excellent.”

Maybe Pat had ranged beyond alcohol. I told her I’d gone skydiving, and in her letter she replied, “You make it sound so great…probably a million times better than dropping acid.”

*

I forged ahead alone and, three years later, entered public life as a judge. Once on the bench I kept my silent promise from the White House Conference on Youth: I visited the institutions where I sentenced people.

*

“Pat drank even more heavily during her job at the Marriott,” Judy wrote, “though at the time, nobody in the family noticed. She didn’t stop for years. Not until a number of incidents landed her in the hospital. The doctor told her if she had one more drink, she would die.”

Pat took one more drink.

About the Author

Anthony J. Mohr’s work has appeared in, among other places, Brevity’s blog, Commonweal, DIAGRAM, Hippocampus Magazine, North Dakota Quarterly, Superstition Review, ZYZZYVA, and several anthologies. A five-time Pushcart Prize nominee, he is on the staff of Under the Sun and is also a senior editor of the Harvard Advanced Leadership Initiative’s Social Impact Review. His debut memoir, Every Other Weekend—Coming of Age With Two Different Dads, is due out in 2023. For over twenty years, he sat as a judge on the Los Angeles Superior Court. Once upon a time, he performed with the LA Connection, an improv comedy theater.