Book Review by Dustin Pickering

“Knowing ourselves, we are beautiful; in self-ignorance, we are ugly.”

-Plotinus

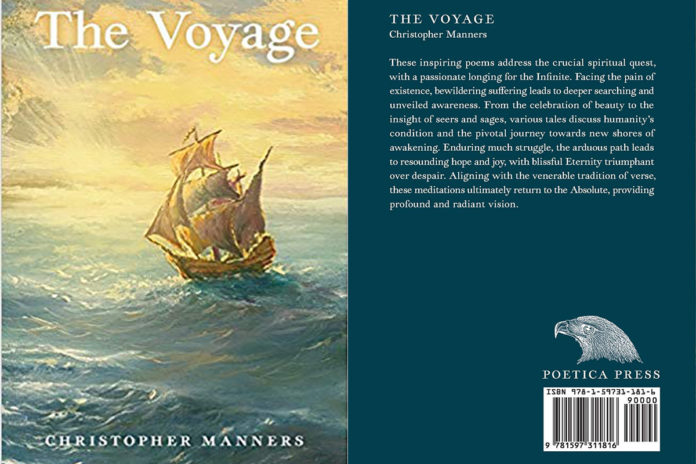

Christopher Manners’ The Voyage is a work of substantial philosophical maturity. The poet is deeply familiar with the classic poetry of Dante, Spenser, Leopardi, and others as well as philosophical constructions of Plato and the Vedas. The voyage itself is metaphorical on many levels. One, the poet illuminates the border between Platonism and the philosophy of the Vedas. The moment strikes as an illumination after a long journey:

“…suddenly I see the convergence clear,

with a flash of wondrous joy to cherish,

between Platonists and Vedantists to revere,

and all the great mystics of East and West,

with their mighty legacy never to perish,

united on that common, devoted quest…”

(“Wandering in Reflection”)

Here it is clearly expressed that there is eternal truth and that many have struggled with it over the ages. The voyage is a metaphor for world expression of wisdom and the discovery of timeless truth. The poet wanders both through the ages and across the seas. Because the poet is of classical bent, he expresses truth as a convergence between great world dominions. The postmodern sense of truth is materialist, dispersed over time and lacking unity, a multifaceted thing of power. Manners’ poetry attends a different march. Truth is personal. It is liberating. In “The King and His Adviser”, for instance, we have a king with insatiable lust for power. The adviser instructs him to build a temple. This poem echoes the facts of Biblical Scripture and the prophets’ fates. The adviser is ignored as the king grows in dominion. This lengthy poem serves as an allegory for human greed and lust. In the end, the king’s hunger is not satiated by dominion. The adviser’s voice returns, reminding him of his admonishment.

“Yet there is no reason to weep,

as truly the temple is actually inside,”

the adviser tells the king. Here we are reminded we cannot go wrong in the true pursuit of wisdom. The poet illuminates Plato’s cave allegory as well.

“beyond the fire you shall rise,

meant those joyful waters to know.”

(“In the Cavern”)

Again, the reader is reminded the pursuit of wisdom is never ceasing yet always rewarding. John Banville writes in The Guardian April 25, 2015: “In The Soul of the Marionette, however, Gray makes a profound observation when he points out that at present the faith most educated people hold to, especially in the west, is Gnosticism. According to the Gnostics of old, the world was created not by God but by a wicked and wickedly playful demiurge, although most people are unaware of the fact. In the Gnostic view, Adam and Eve were right to eat the forbidden apple, and the Fall of Man was in fact a fall into freedom, ‘a fall’, as Gray beautifully puts it, ‘into the dim world of everyday consciousness’”. Manners’ tells the reader of the fall, yet his view sharply contrasts with this prevalent view. In “The Builder” we are led to believe the view of God Manners presents is not one of a “playful demiurge”—that playful demiurge is Man himself. The poem is an allegory for the human condition, the ceaseless striving for knowledge and work. While Manners sees knowledge the same way as the Gnostics, he views God as an everpresent reality unlike most educated contemporaries. The builder is punished for burning the woods to the ground much in the same way Adam and Eve were exiled to labor outside of Eden. Here Manners restores the understanding of classical poetry to Christian terms. According to Banville, most educated people today believe God is akin to Loki, essentially a personification of impersonal life forces. However, Manners indicates that God is the supreme reality and it is we who lack understanding. Our quest for gnosis is ultimate but most people shy from it to pursue worldly attainments. We are still unique and valuable to God individually. Again, in “Wandering in Reflection” he writes: “so even in that one united state, nothing must be lost of each soul’s glory.”

The pace and rhythm of each poem reflect a structured approach. One may finds hints of Spenser’s The Fairie Queen in the use of past participle. The poet’s approach to life is not entirely optimistic or pessimistic. Suffering is inevitable and human nature unchangeable. The eternal verities are proof of the existence of higher perception, and it is our good grace to be made aware of them. Human freedom is dependent on the pursuit of self-knowledge, mastery of one’s mind. This view is conservative in nature and founded on a classical perception of the world. Prometheus is a liberator in granting us the capacity for self-reflection. Manners writes:

“that light of inner knowledge which he taught,

the way to freedom from this cage to scorn..”

(“The Gift of Prometheus”)

“The Founding of Croton” is another allegorical tale. Here we see the illumined character of the poet. He presents us with an understanding of Plato’s Republic that many libertarian scholars share. The Republic is allegorical in nature and Plato did not intend for it to represent political realities. Plato’s ironical nature has an imaginary Socrates banish the artists, among other totalitarian effects. Croton is founded by a foreigner; yet another metaphorical use of exile. We may imagine Plato as an original postmodernist, seeing the lacunae as the true meeting ground of the wise. The philosopher king is central to the city—he embodies its wisdom; so, why are the artists, those rapscallion seekers of truth, exiled? Does this symbolize what Foucault called dispersion? The laws are a disunited body but the king, who may act benevolently as a Taoist ruler, is the true angel of wisdom. His motions direct the city in like manner to the human brain directing the body. He is a symbolic essence, the core. Neurologists have discovered the mind and body are not separate. The human brain, extraordinarily complex, is made of divergent physical components that operate in harmony. In the poem, Pythagoras is the philosopher king. He is “meant with the underlying Source to unite” and tame the mysteries of the cosmos. He represents knowledge itself and the powers by which we achieve it. We are reminded that political realities can be employed metaphorically. Hobbes uses The Leviathan to explore human nature and the struggle for the existence of the state. In “Leviathan as Metaphor”, Samuel Mintz suggests the leviathan is symbolic of intellectual pleasure. The State is created to insure security for all, thus enabling the arts and intellectual pursuits. Perhaps Plato banished the artists to demonstrate the necessity of human freedom. In The Laws, anarchism is the ideal system but the laws bring us closer to the ideal in shaping our state. Why else does his totalitarian State suggest? Without the arts, what would the State be needed for? What appears to be a totalitarian system in Plato is actually an overarching metaphor for the nature of life and the place of Man within it. The fire of the cave is what hurts us; it is illusion that distracts us from our inner wisdom and intellectual pursuit. The cave allegory, presented in The Republic, is discovered to be a metaphor of scale within the broader discussion of justice. What is the pursuit of justice without truth? Is truth relative? In The Republic, Plato also tells us human affairs are not to be taken seriously. So we are back to Manners and his defense of solitude and the joyful wisdom.

The poem that is most striking is “The Search”. A carefully disguised allegory for return to oneself, this poem invokes the depth of love. A man seeks his lost love across the seas until he finds her and “he then did bring / glorious Caterina into the sun”. At the poem’s end, “their eternal souls did align / with that lasting love Divine.” Easily seen as a Romantic poem, “The Search” is the most lucid example of Manners defining the return to oneself as uniting with wisdom and the Divine, or Absolute. The loved one becomes a symbol of the infinite search and yearning within the human soul, the insatiable desires that torment and guide us on our quest for ultimate truth.

Christopher Manners is humble enough in his work to remind us that the pursuit of wisdom is the deepest happiness, not its attainment. Pleasure and distraction, power and empire, all these things are nothing without the inner light and the solitude it brings. In a profound sense, knowledge is restoration. We left the world of beauty and light and inevitably will return to it. Gnosis is the fact of that pursuit.

The Voyage will take you on a journey through the intricacies of your mind, the East and West will be bridged, your philosophy of being will become. The Voyage is an important work in our world today because it upholds the eternal truth and tells us God is our friend, not a jester pretending in order to fool you. Wisdom exists and it is folly that unravels it.

About the Poet

A Canadian poet, Christopher Manners has 2 poetry books published by Poetica Press, an imprint of Sophia Perennis. Residing near Toronto, he has a Bachelor of Arts with Honours from York University. Revering the beauty of poetry, he has always cherished this sacred art, finding solace and inspiration. Manners is also the founder of Poetryimmortal.com, a poetry blog dedicated to the classics.

About the Reviewer

Dustin Pickering is founder of Transcendent Zero Press, a publishing company based in Houston, Texas. He featured for Houston’s most popular reading series Public Poetry in 2013. He frequently attends Austin International Poetry Festival. He is author of The Daunting Ephemeral and The Future of Poetry is NOW: Bones Picking at Death’s Howl, available on Amazon. His book Salt and Sorrow was published by Chitrangi Publishers in Calcutta, India, and his philosophical prose book A Matter of Degrees was published by Hawakal Publishers in early 2017.