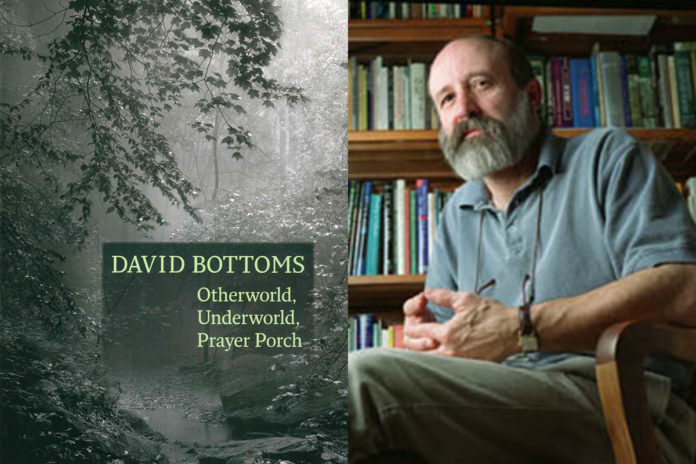

Book Review by Lynn Alexander

Just as Dante’s journey to the underworld begins in a dark wood, the ghosts of loss arise out of the woods, rivers, lakes and fields in David Bottoms’s tenth volume of poetry, Otherworld, Underworld, Prayer Porch. The landscape of the poet’s memories of Canton, Georgia is inhabited by spirits of people he’s known—a grandfather with his a tackle box full of lures who rarely catches a fish; a dying father who, tired of hospitals, pulls a gun on ambulance workers as they try to coax him out of the house; a friend’s dead brother whose cellphone is slipped in his suit pocket before the coffin is closed, ringing twice during his burial and mortifying the sister who put it there.

An Absence begins with a meditation on what Bottoms gleans is of crucial importance as he reminisces:

Near the end, only one thing matters.

Yes, it has something to do with the moon and the way

the moon balances so nervously

on the ridge of the barn. This is the landscape of my childhood—

Here we see the first appearance of the fox, a nighttime prowler who is rarely seen despite the poet’s best efforts, representing the dark powers of the unconscious known only by the tracks glimpsed in waking moments.

During the night, Bottoms sets out to the backyard with his dog, Jack, and confesses:

Sometimes when my wife and daughter are asleep

I stumble outside

with our dog at three or four in the morning to piss in the yard…

This is when I empty myself of anger and resentment,

and listen to them puddle

in the grass at my feet…

Jack runs the fence line and trots out

of the shadows, panting, to piss in the grass beside me.

Often in his eyes there is more to envy

than anything human…

He subjectifies his experience of the creatures he encounters along the way, whether it be dogs, rabbits, snakes, gators or horses. In A Nervous Boy, the poet aims his rifle at a rabbit as his grandfather holds the stock to his shoulder:

I hadn’t wanted to shoot the rabbit.

It sat on a ridge of the pasture, stiff ears reaching for the sky,

and even from that distance I could see it trembling…

We see a similar subjectification of a captured gator that crawls out of Lake Allatoona:

Where I was raised anything unusual became a spectacle,

like this four-foot gator

held by Lee Spears behind the South Canton Trading Post…

Years later, in Florida I paddled over dozens of them on Lake Talquin, their eyes on water

like small balls of moonlight.

Not one ever rose to the boat, or even stirred,

which makes me wonder now

why this one, jaws wired shut, keeps gnawing at me with its desperate eyes.

These boyhood experiences carry over into Bottoms’s later experiences. But in all truth, sacred landscapes can contain frightening creatures, real and imagined, poisonous and benign. When he sees his dog harassing a harmless King snake on the prayer porch, he moves to protect it, a habit he formed in childhood by imagining the otherworldly essence in all sentient beings:

…and (I) watched it sidle across the grass

and thought of a time I would have taken more joy

in its appearance, would have felt it

to be something miraculous,

a necklace, say, fallen from a witch’s neck,

suddenly come alive

and slithering into the brush.

On a walk in the mountains with his dog, he spots a venomous moccasin and states:

I could have killed the snake.

I had a pistol in my belt, a 9mm, a Smith & Wesson,

accurate, deadly, and I was a good shot.

Yet, he becomes fascinated by it while deciding whether or not to let it go:

I studied the moccasin for a moment longer—

the fat and terrible muscle of him, his black scales rippling

while a small wind

brushed his back with shadows

Instinctual fear arises in An Old Enemy when, by moonlight, he sees something coiled at the root of a cherry tree:

It didn’t rattle or move, and I thought it might be dead,

then the fat tail twitched

as a slight wind washed the root with shadows.

I backed away slowly, looking for the shovel

I kept leaning against the fence.

It wasn’t there. So thinking “omen”, I left the snake

and walked back to the house.

This morning I saw my mistake…

Written mostly in single lines, open couplets and tercets, these poems express the natural world as kinfolk. This perception departs from Descartes and behaviorists who view the earth—trees, oceans and animals (other than mankind) as machine-like, without souls, thoughts or feelings, and whose primary value is their utility. This perception has fueled the exploitation of the natural world and led to the extinction of wildlife. Bottoms, however, returns us to the sacred order, to reverence for the connectedness human beings have with the natural world, and the moral sensitivity of viewing all earthly beings as soulful.

Yet, where there is light, there is also darkness. In Sunset Syndrome, we find an entrance to moonless gloom when his aged mother calls him at four a.m. to say nurses at the hospital are trying to kill her:

…all those hysterical gurneys clacking

down the hall. Nothing would convince her otherwise—

watch the elevators, listen

to the screams. No one damned to the basement

ever comes back.

When his mother is moved to a nursing home, she grumbles, this place is full of old people. In an attempt to re-direct her attention as they cross the threshold of automatic doors that leads to her room, Bottoms points out a singing bird on a branch. But she isn’t moved and responds, It’s only a sparrow. While she complains about an aide who swipes an uneaten apple off her lunch tray and worries about dust gathering in her china cabinet,All she had to do was lookto find grace and meaning,despite strange new surroundings.

In The Moon My Mother Shot For, Bottoms illustrates the pointlessness of striving for what society values by illuminating how his mother scraped for twenty years to buy a full-length mink coat and two-carat diamond ring but had no place to wear them in Canton, Georgia:

All those lovely nights

When the full moon hung like a ballroom chandelier

over the used-car lot across the highway, that mink hung

wrapped in a sheet in their bedroom closet

and the diamond dulled quietly in its velvet box

in a vault at the Etowah Bank.

In No Voice in the Trees, Bottoms muses on the possibility of supernatural experience within the natural world. While sitting ina secret place out near the fence under cherry trees, he contemplates how wind, crickets and tree frogs give rise to voices in the trees:

Wind brushes the cherry branches and suddenly I’m sitting

quietly with my father

who loved to rock at night on his backyard deck and listen

to the wind sweep in oaks. (whose voice

in those trees?)

We are transported to the realm of the divine as he describes the holiness of his wife’s face:

Sometimes when she sleeps, her face against the pillow (or sheet)

almost achieves an otherworldly peace.

Sometimes when the traffic and bother of the day dissolve

and her deeper self eases out, when sunlight edges

through the curtains and drapes the bed, I know she’s in another place,

a purer place, which perhaps doesn’t include me,

though certainly includes love, which may include the possibility of me.

And we witness the transcendence of faith in the afterlife in his repeated return to the image of Christ Pantocrator, an icon on a panel which hangs between two screens on his prayer porch.

When we reach the final poem, A Scrawny Fox, we come full circle and recognize the end as the beginning:

Near the end, only one thing matters.

Yes, it has something to do with the moon and the way

the moon balances so nervously

on the rooftops of neighborhood houses. You remember the landscape

of your childhood, your house and yard,

the yards of your friends. Near the end, though,

only one thing matters…

and nothing, not even the fox, moves as quietly.

In Underworld, Otherworld, Prayer Porch, we enter a landscape that’s worn a path through the poet’s heart. Bottoms finds a way to enter eternity in the only way a mortal can—by remembering the past and by being remembered. This is the secret of the underworld—that spirits of people, animals and landscape live through us as long as we remember—appearing as voices in oaks when the wind blows, in moonlight gleaming through sacred forests, or in our own backyards, out near the fence, under the cherry trees.

About the Author/Poet

David Bottoms’s first book, Shooting Rats at the Bibb County Dump, was chosen by Robert Penn Warren as winner of the 1979 Walt Whitman Award of the Academy of American Poets. His poems have appeared widely in magazines such as The New Yorker, The Atlantic, Harper’s, Poetry, and The Paris Review, as well as in sixty anthologies and textbooks. His most recent book of poems, Otherworld, Underworld, Prayer Porch, was released by Copper Canyon in the spring of 2018. Among his other awards are the Frederick Bock Prize and the Levinson Prize, both from Poetry magazine, an Ingram Merrill Award, an award in literature from the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters, and fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Guggenheim Foundation.

About the Reviewer