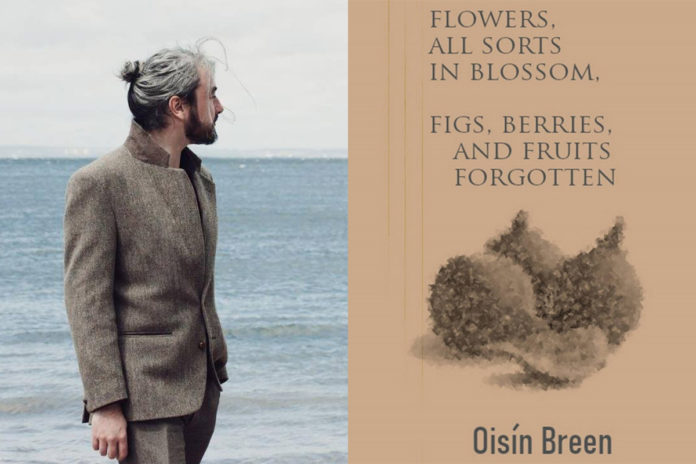

Book Review By David Carpenter

I enjoy being challenged, and this review certainly presented challenges. I am not a reviewer by trade, and this is, in fact, the first full book of poetry I’ve read for several years. Nevertheless, I am thankful to Mr. Breen for rekindling my delight in tantalizingly off-kilter metaphysical poetry.

Indeed, Breen, an Irishman with a good dose of Edinburgh fused into his being, is a metaphysician’s physician. He tells it how it is, but he doesn’t make it easy, although where would the fun be in that?

The first thing noticeable about this collection is its unfeasibly long title, and, to be honest, this gives a huge clue as to what follows, namely three epic-length poems on being, knowing, identity, time, space, death, life, sex, drugs, childhood, Dublin, the gods, and music … the list goes on.

This triptych of poems begins then with an even longer title: ‘Isn’t the act of placing flowers on a tomb a gesture of bringing a little life back to the dead?’

It is perhaps best to explain first what it is, and what it does, rather than simply break it down line by line. Reading this poem, I feel I’m possibly reading a natural heir to the modernists of yore where memory and desire are mixed by an alchemist and presented as the only way we perceive reality.

The opening verse is stunning in its beauty, begging immediately to be read aloud:

‘Memories… silk heavy in the russet wind, like sinuous leaves with ice-cracked spines’.

This is followed by the first of several choral invocations, and the first part of several sections ends in a lingering refrain.

Such an approach, although perhaps not typical to contemporary poetry proves richly rewarding. Poetry should spark a sense of musicality when read, and Breen ensures that it does, as words bludgeon the reader from the off with sound. ‘Sun-whetted stone‘ conjures up images of sharpened knives, and appetites, supine in glistening sunshine; whereas ‘each instance of kenning is a quickened sapling’, brings Scots, Old Norse and Old English to the fore.

This poem thrives on a simple basic fact, it is full of excellent and memorable lines: ‘My clothes hang heavy with the flavour of wet fire,’ or: ‘Just silence in the rapture of the mulch.’

Furthermore, Breen’s use of verse and prose excellently serve the stories the poems carry. These stories pertain to a man trying to divine his future, reminiscing over what it felt like to be young, as well as a particularly poignant story of a bullied child who in turn enjoys and is relieved by bullying in return, only for it to turn to ash. These stories are truly moving.

As the first poem in Breen’s triptych reaches its conclusion, the style shifts into short prose paragraphs. Reading them, it is hard not to compare the approach to the Catechism chapter of Ulysses, not because of any similarity in questions and answers formatting, but because it carries a sense of kindness and a sense of circularity in its dense prose that is highly palpable in both Breen’s work and Joyce’s:

‘I stand… and write and write and write and write, and I collapse holding a rotten oar, ah that I love it all to the point of breaking’.

Throughout Breen’s debut collection, one thread in particular is worth noting, that is the influence of a pantheon of gods, an influence that moves from the background in the first poem, to the foreground of the second, ‘Dublin and the Loose Footwork of Deity’.

If ‘Isn’t the act of placing flowers on a tomb a gesture of bringing a little life back to the dead?’ is a prelude to this foregrounding of the gods, it uses Barû, a god of divination, as a bridge between memory and desire. But if this first poem anticipates what is to come, ‘Dublin and the Loose Footwork of Deity’ is nevertheless an opera. Each part carries the name of a different deity, and the city of Dublin too serves as a god, perhaps the god of the whole work. Indeed, through this device Breen challenges us to assess how all life shapes our self-identity.

The loose footwork of this poem, disciplined as it is, is capricious in its scope and form, encompassing the minutiae and grand history of life, where the grandiose meets the temporal and all are one and the same: ‘Remember, my city is built with your grand father’s bullet wounds’ juxtaposes nicely, for instance, with a reminiscence on sexual exchange ‘in a whirligig of loving’ as the protagonist finds the trade of partners with his friend tastes ‘bitter on our lips’.

Part four, ‘Gula Innana’ – a mother goddess, warrior, giver of mercy, old, powerful yet perceived as young and beautiful – is, to me at least, the central part of ‘Dublin and the Loose Footwork of Deity’, if not the whole book. Introspection represented by verse, ‘for who better in the knowing than the I who is known?‘, vies with history that is written in short tight prosodic paragraphs to begin with, then gradually breaks down once more into verse. We move from the 14th Century to the 19th Century and back to the 18th Century in a kind of eternal love story until such movements are declared ‘the derelict martyr in this poetry of space’, at which point Breen plunges the reader back into metre, then once more prose, and back and forth in a dizzying sequence that also takes in matters of the law, the nature of power, taxation, and Dachau. Then, as it starts to peak, the sequence breaks away into a theatrical rendering of a bar at 3.30 in the afternoon, where we have as fine a rendition of afternoon drinking as I have ever read. Indeed, for all the Breen is about l-a-n-g-u-a-g-e, very much with a capital L, his work is totally infused with real-world happenings to which we all can attest.

This enjoyable downward spiral-structure within the poem’s fourth section is, in fact, reflected increasingly as the poem progresses. Dublin, the central god, also stands exposed: ‘her arse, her gaping maw’ with echoes of Joyce and Beckett once more coming to the fore, until finally the piece closes with a fascinating litany, as opposed to a list, of the gods, concluding with this bitter note:

‘Dublin / Dublin / Dublin Town / Heavy am I with your streets and their telling’.

The third and last poem in the collection, ‘Her Cross Carried, Burnt’, bookends the collection well by bringing loss full circle. If the first poem is for the protagonist’s father, then the book’s last is surely for the mother. Again, as with the two pieces preceding it, ‘Her Cross Carried, Burnt’ is epic in verse and metre, taking in history loss, love, birth, corruption and redemption; and, although the gods do not play a part in this poem, they are very much a background figure that one is constantly called to remember through incantations, penitent recantation, and this last poem is deeply infused with a sense of prayer.

‘Her Cross Carried, Burnt’ is also the most metaphysical and the most musical of the three pieces in Breen’s collection. It throbs with an unearthly rhythm that in many ways recalls Euripides’ The Bacchae.

Throughout this piece, Breen employs metaphysical imagery to embark on introspection, with tautology becoming a literary device to emphasise shifts in the internal mindset of his protagonist:

‘But there is no turning back, where we are that which we are, and we are what we have become.’

Such lines continue Breen’s evident fascination with memory and desire, as evinced by these that follow soon after:

‘Humanity, notionally a scarecrow, dispenses fear. It is in this way that we can find ourselves finished, done, and our thoughts cast in wrought iron.’

Ultimately a huge part of this final piece, is, in fact, a meditation on forgiveness, which completes Breen’s cycle aptly.

Indeed, as ‘Her Cross Carried, Burnt’ reaches its end, the circularity of the overall collection is so clear that it is difficult not to think of Yeats’ ever-widening gyre, Joyce’s recirculation, or Beckett’s weariness of his motifs. This circularity then rises into a highly rewarding crescendo of despair, but above all hope – you’ve been the grist for the mill and you’re safely through to the other side. As a result, Flowers, All Sorts in Blossom, Figs, Berries and Fruits Forgotten, above all else, strives – and mostly succeeds – to declare itself a thing of beauty.

It is my conviction that literature, be it poetry, plays or novels, or art in any form for that matter, should challenge the participant and make them see the world anew. On this level, Flowers, All Sorts in Blossom, Figs, Berries and Fruits Forgotten certainly makes its mark with both quality and distinction, although it must be said that the sheer density and linguistic play Breen engages in throughout makes it a challenging read.

About the Poet

Oisín Breen is a 35-year-old poet, part-time academic in narratological complexity, and a financial journalist covering the US-registered investment advisory sector. Dublin born, Breen spent the last decade living in Edinburgh and has lived, among other places, Damascus, and Prague. His widely reviewed debut collection, ‘Flowers, all sorts in blossom, figs, berries, and fruits, forgotten’ was released Mar. 29 by Hybrid press in Edinburgh (https://hybriddreich.com/oisin-breen/).

Primarily a proponent of long-form style-orientated poetry infused with the philosophical, Breen had a number of poems published in his early twenties mostly in online magazines, before taking time out to hone his craft, since then he has been published both in written and audio formats in a number of journals, including the Blue Nib, Books Ireland, the New English Review, and Dreich magazine. At present Breen also has forthcoming poetry in the Agonist, Metaworker, and La Piccioletta Barca.

About the Reviewer

David T. Carpenter MSc is an Edinburgh-based English teacher, and Director of Studies, as well as an occasional writer of prose.