By Kenny Chumbley

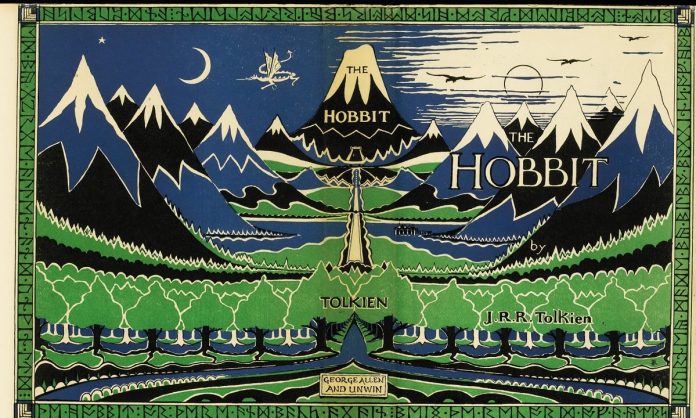

In October 1936, a manuscript for a children’s book arrived at the office of the London publisher Allen & Unwin. Stanley Unwin, the firm’s chairman, who believed children were the best judges of children’s books, asked his ten-year-old son, Rayner, to read the story and report back. Rayner’s conclusion was that the story “is good and should appeal to all children between the ages of 5 and 9.” Rayner was right about J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit being good, but he was considerably off on the age range to which it would appeal.

“There is no question,” wrote Michael Drout, that “Tolkien is regarded as the greatest fantasy writer in English and that his Lord of the Rings is considered the masterwork. There is not even any real challenger.”(1) Drout’s conclusion, I think, is beyond dispute.

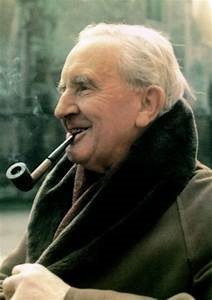

The biographies tell us that Tolkien (1892–1973) was an unassuming, private man, who was devoted to his family. He was a gifted philologist, an inspired storyteller, a Roman Catholic, and a combat veteran of World War I, who was hospitalized with a serious trench disease. After the war, he worked on the Oxford English Dictionary, and his interest in philology and linguistics ultimately led to a professorship at Oxford. C. S. Lewis was a close friend, but, surprisingly, both were very critical of the other’s efforts at writing fantasy.

During his lifetime, Tolkien was a celebrated scholar, but his enduring fame traces to words he scrawled in the early 1930s, “In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit.” Not long after publication of The Hobbit (Sept. 21, 1937), and its adventures involving Bilbo Baggins, he began work on a sequel, which would take nearly twenty years to complete. The Lord of the Rings(LOTR), which centered on the adventures of Bilbo’s nephew, Frodo, is linked to The Hobbit by a ring that made its wearer invisible. Both Plato (in his second book of his Republic) and the Norse Nibelung myth (popularized by Wagner) spoke of such a ring, but there is no evidence Tolkien borrowed from either of these sources to write his story. Rather, he said the imagination that created the LOTR grew “out of the leaf-mould” of his early life experiences.(2)

In Tolkien’s stories, profound truths lurk everywhere. He once noted, for instance, “that we are here, surviving, because of the indominable courage of quite small people against impossible odds” – could there be a better description of the hobbits? Frodo’s mortal wound, inflicted by the wraiths, reminds of the terrible price some have to pay for the good of others. And LOTR, which is a quest not to gain something but to relinquish something (i.e., power), well illustrates Lord Acton’s maxim that power corrupts; at the last, not even the noble Frodo could freely surrender the ring.

I acknowledge that the brevity of this essay doesn’t do justice to Tolkien, but maybe this will be mitigated by the expansiveness of my wish that Tolkien’s fairy tales—which “rule them all”—be long remembered.

Footnote:

(1) Of Sorcerers and Men, Tolkien and the Roots of Modern Fantasy Literature (Barnes & Noble, 2006), 15.

(2) Humphrey Carpenter, J. R. R. Tolkien, a Biography (Houghton Mifflin, 2000), 131.

About the author:

Kenny Chumbley, a native of the Illinois prairie, is a minister, author, and publisher. He has authored one children’s story (Ol’ Pigtoes) and two fairy tales (The Green Children, the Literary Classics 2017 Enchanted Page Award recipient for best children’s storybook, and The Goblins Who Stole a Gravedigger, an adaptation of Charles Dickens’ first Christmas ghost story). He has also written and produced two musical plays based on his two fairy tales.