“It sounds uncommon nonsense.” The Mock Turtle

Among the storied authors of children’s fantasy literature, possibly none achieved greater fame with less effort than Lewis Carroll.

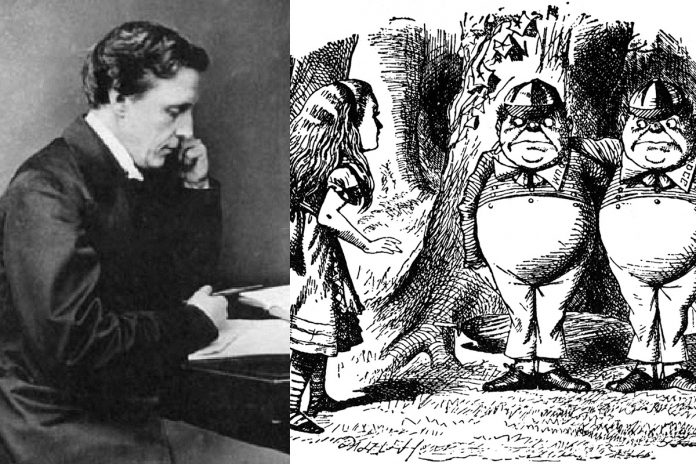

Charles Dodgson (1832–1898) was a nondescript Oxford mathematics lecturer, but a born story teller, who wrote a smidgeon of children’s stories under the pen name Lewis Carroll. Of these, only two—Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and Through the Looking-Glass (1871)—are much read today. Per Chesterton,(i) the Alice stories were written during intervals of lucid lunacy, and after reading them, you wonder what to make of them. My take is that they can be read on two levels—the playful and the profound, but mostly the playful.

On the surface, the Alice stories are nonsense piled on nonsense; larks to be read with childish simplicity and glee at the author’s unbounded imagination. If Carroll appears autobiographically in them, surely he is the White Queen. “‘I’m just one hundred and one, five months and a day.’ ‘I can’t believe that!’ said Alice. ‘Can’t you?’ the Queen said in a pitying tone. ‘Try again: draw a long breath and shut your eyes.’ Alice laughed. ‘There’s no use trying,’ she said: ‘one can’t believe impossible things.’ ‘I daresay you haven’t had much practice,’ said the Queen. . . . ‘Why, sometimes I’ve believed as many as six impossible things before breakfast.’” Carroll could imagine the impossible as easily as the White Knight could fall off his horse, and Wonderland’s enchantment is its upside-down logic, topsy-turvy word plays, and relentless non-sequiturs.

But there’s something deeper than this, for the Alice stories use nonsense to parody the nonsense that permeated Victorian conventions. Carroll’s nihilistic tales are wonderfully anti-establishment, wherein a societal insider writes as an outsider and uses absurdity to skewer the pretentions of a society that insist edits absurdities be taken seriously. The best way to answer pretentiousness—especially, establishment pretentiousness—is never to argue with it but to laugh at it. And this Carroll did splendidly (even if he didn’t realize it).

Of special interest to authors hoping to get their story published is the fact that the very first edition of Alice in Wonderland was self-published. Carroll paid Macmillan £600 (then an enormous sum) to print 2,000 copies (as well as £138 to John Tenniel for the illustrations). He fully expected to lose money on the first printing and did, but subsequent printings/editions finally returned him a profit. The self-published first editions of Alice in Wonderland are the Holy Grail for book collectors. Only twenty-two copies are known to exist, and they sell for millions whenever auctioned.

If you’re ever at a loss about what to do on a sunny summer’s afternoon, you might heed the Walrus’s suggestion that The time has come,/ to talk of many things: / Of shoes—and ships—and sealing wax— / Of cabbages and kings—.

Footnote: (i) “The 100th Birthday of Nonsense,” published in the January 24, 1832 edition of The New York Times Magazine.

About the author: