Book Review By Laura Lush

To say that it is a brave undertaking to tackle an epic is an understatement. Blame T.S. Eliot, who held the epic as a poet’s defining standard of greatness. And while history is full of great epic poets, most contemporary poets stay clear of this ambitious poetic form. However, some poets / literary works who/which have succeeded in the epic—or “verse novel”—are Scotland’s Robin Robertson (The Long Take, 2018); Derek Walcott’s Osmeros (1990); and Canadian poets Anne Carson’s Autobiography of Red, (1998 ) and George Eliot Clarke’s three-part epic, Canticles I and II (2016, and 2017).

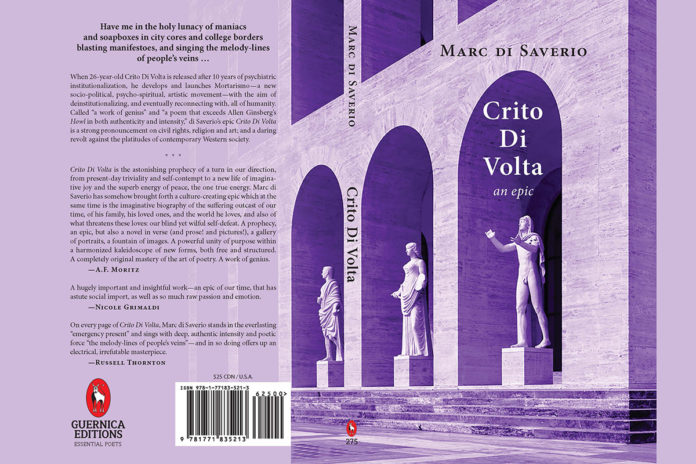

Guernica Editions’ Marc Di Saverio is one more contemporary poet to hit Eliot’s formidable mark. In his masterfully written 174-page epic, Crito di Volta, Di Saverio illumines the genius and suffering that imbue the characters of the soul-destroying “sanatorium” as he exposes the malevolent forces that attempt to silence their voices. Di Saverio loosely adopts Plato’s notion of freeing the imprisoned Socrates—but in this Crito, it is the unjust and inhumane social construct of the “’insane’” that Di Saverio seeks to correct and free. As the protagonist Crito says, “There is no better way to quiet the voice of God and his true prophets than to create an apartheid between the society of the ‘sane’ and the society of the ‘insane.’” And while writing about the institutionalized experience is not new—Sylvia Plath, Ann Sexton, and Ezra Pound being immediate standouts as well as Canadian Shane B. Nelson’s memoir Gunmetal Blue (2011) — what makes Di Saverio’s take on the institutionalized so remarkable is his particular Homeric eye that sings the full range of the human spirit in this compulsively readable epic.

Crito di Volta triumphs as a torrent of shifting fetes of metrics and arguments that mimic the lows and highs of the human spirit. Di Saverio’s poetics are borne out of an irrepressible desire to invoke the muted voices of the institutionalized: “Let’s breathe the afflatus of the ‘manics,” “let’s dance the steps of the ‘schizophrenics, channelling a music we will never hear.“

Crito di Volta possesses a modern fusion of Whitman’s “yawp”, Pound’s outspokenness, and the psychic hell of Dante’s Inferno as the characters of this epic rise and self-immolate in alternate psychic rhythms. Breathtaking lines of poetry spark every line as Crito “sing[s] into overdrive” with a voice that brims with an “electricity, that filamentous/force” of the soul. Equally remarkable is Crito’s ability to pay homage to both the religious and scientific in this epic. Sometimes his voice is driven by God– while others it is driven by science, as in the Russian scientist, Velikovsky, whose theory on electricity allows Crito’s voice to lightening-rod through every line.

However, the epic does not begin in a lofty epic form but rather with an email from Crito di Volta to Flavia Vamorri, Crito’s muse and the “flame” that sparks his passions, poetic genius, and eventually his attempt to overtake the massive psychiatric hospital. Indeed, Flavia and he are painfully “hunchbacked in misfitness” as they bond in their understanding of how the psychiatric patient is grossly stereotyped; his voices feared; his psychosis unbearable; and his exuberance threatening. And it is precisely this “misfitness” that emboldens Crito and Flavia to heroically bust open this misguided label as their psychic and physical selves are subjugated to the mercy of exploitive nurses, mind-numbing psychotropics, and ECTs.

But this epic does not succeed by story-line alone. Di Saverio is a master of figurative language, delighting the reader time and time again with sensory-charged similes and metaphors: “Like blood through a cut we break through the smoke”, “I bow like a dew-drooped vermillion tulip”, and “Like an old man’s map of the world I fold.” His lines are couched in a muscled and musical metre that riffs with assonance and consonance: “before we smash and re-map and dash” and “the sublimely unsingable /chimes.” Equally stunning are the simple natural images that shine their presence in this epic: “A breeze of flower-blends enters her room”, “ a wind of ash,” and “I pause to hear the little wind.”

Di Saverio attends as much to form as he does to content, never forgetting that the story he needs to tell is one that only can be told through these small and startling lifts of language. As the epic moves forward, Crito and Flavia solidify their unbroken commitment and bond to one another: “Now I go forward with foot-soles of the wind…/Flavia, don’t let me be taken until completely given.” So Crito, Flavia and their colourful ”ward mates” (Ivan, the Afghan vet, and Tristan Dion, who dreams of being a boxer ) launch their revolution in the sanatorium, fight valorously—but eventually, surrender, as Crito realizes that the battle has to come to an end. After the failed coup, Flavia succumbs to her own demons three-quarters into the epic. Returning to the email convention that begins the epic, Flavia’s suicide note is emailed to Crito. Two simple lines that begin the email say it all: “I’m spent/I’m ‘completely given,’ Crito.” And then the words that no one wants to hear: “Crito, I can’t…Crito—I’m going.” And in five lines, she encapsulates the hell of so many of the institutionalized:

The failure of my mission, the PTSD, the limitless mania, the Infinite depression, the pointless fluctuations, the stiff stupors, the emotionless psychiatrists, the endless torment, the blatant incurability, the infinite stigmas, the ultimate failure, the bottomless bitterness, are all too much for me now.

Yours,

Flavia

The strongest poems arrive after Flavia’s death, where Crito somehow makes peace with Flavia’s passing in a poem that he pens for his friend, Amos:

My spirit is an open city now.

The minute-men of my last fight are dead.

My last-born Hope is shot inside her bed.

My nape of Faith now takes a bloody bow

Before the scattering sides of the war:

the Stranger and the humankind, who stoke

His heart with my dying hand, choke

my ministers, then open my red scar.

I feel my memories flood the streets

like children after fire-testing bells—

and I’m gone…I am now the morning star;

my centre burns for you though I’m so far.

And though you mar my name now, I am still

your guide. Forgiving you is my last will.

We reach for poetry in an attempt to better understand ourselves and the world around us. And we reach for poetry to see the world in a new way. But it is a rare poetry book that does all that and leaves us mourning the characters as well. To feel that we have somehow “known” and “connected” with Crito and his brave comrades, understood their plights and challenges—cheered them along in their battles—makes this epic so much more human and relatable. Di Saverio’s Crito di Volta proves that poetic achievement does not preclude readability. This is an important and timely book at a time where COVID19 has brought us to our collective knees, forcing us to pause, reflect, and to look at our selves and all that as a society we pay lip service to but still ignore: the homeless, the institutionalized, the disenfranchised. And in a prophetic Yeats-ian image, Crito leaves us with his final words:

O humankind revolving like a gyre—

O martyrs before me who challenged the fire—

O those of you who’ll come and up-stand—

At last I know just who and what I am:

The irony is that there is an open colon at the end. Somehow, I believe that Di Saverio has left it up to us to fill in what comes next—those among us who are also brave enough to “challenge the fire.”

About the Author

Marc Di Saverio hails from Hamilton, Canada. His poems and translations have appeared internationally. In Issue 92 of Canadian Notes and Queries Magazine, Di Saverio’s Sanatorium Songs (2013) was hailed as “the greatest poetry debut from the past 25 years.” In 2016 he received the City of Hamilton Arts Award for Best Emerging Writer. In 2017, his work was broadcasted on BBC Radio 3, his debut became a best seller in both Canada and the United States, and he published his first book of translations: Ship of Gold: The Essential Poems of Emile Nelligan (Vehicule Press). Forthcoming is his epic poem, Crito Di Volta. He is currently writing his first novel, The Daymaker. Di Saverio studied English and History at McMaster University, but never took a degree, due to illness. He is the son of Carlo Di Saverio, the scholar and teacher who studied Linguistics and Languages at University of Toronto (M.A.,1981). Di Saverio’s poem, “Weekend Pass”, was adapted into the movie, CANDY — directed by Cassandra Cronenberg, and starring the author himself — which went to the Toronto International Film Festival in 2013.

About the Reviewer

Laura Lush (born 1959) is a Canadian poet and short story writer. She is most noted for her 1992 poetry book Hometown, which was a shortlisted finalist for the Governor General’s Award for English-language poetry at the 1992 Governor General’s Awards. She has since published the poetry collections Fault Line (1997) and The First Day of Winter (2003), and the short story collection Going to the Zoo (2003).