By Kenny Chumbley

No one familiar with Victorian literature would rate Charles Kingsley’s books among the very best except, maybe, his children’s fantasy, The Water-Babies.

Charles Kingsley (1819–1875) was an Anglican clergyman noted during his life for his activity in five major areas.

- At his center was his Christianity. When invited to preach to the Royal Family at Buckingham Palace, he asked what kind of sermons the Queen preferred and was told she liked them direct and short. So well did he meet these criteria that he was appointed royal chaplain.

- Kingsley was passionate about natural history as seen in his book, Madam How and Lady Why. Influenced by Darwinism, he sought to accommodate evolution within a Biblical framework.

- He was prominent in the Chartist Movement, which advocated and agitated for improved conditions for the working class.

- He was a poet but not a great one; yet When All the World Is Young, Lad is a great poem.

- His adventure stories like Hypatia and Westward Ho! were especially popular. Recalling his boyish excitement over a Kingsley tale, Andrew Lang wrote, “What a slayer was Hereward the Wake! When that romance came out in Good Words[edited by Geo. MacDonald], we boys, on a Sunday, would reckon up Hereward’s bag for the month. In one chapter he did not killed anybody, he only ‘thought of killing’ an old woman! This was disappointing to his backers!”(i) (A town in southwestern England is named after Westward Ho! and is the only town in England having an exclamation mark as part of its name.)

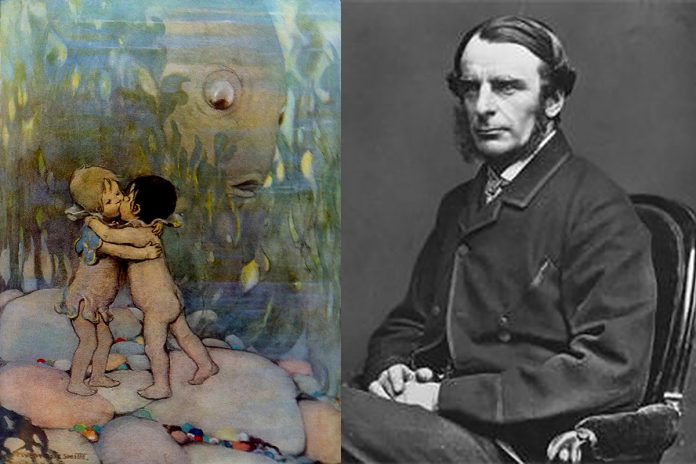

In 1862, Kingsley’s wife urged him to write a story for their fourth child as he had done for the first three. Charles always insisted that the result was nothing more than a fairy tale not to be taken seriously, but, in fact, The Water-Babies incorporated each personal proclivity noted above. The story, which tells about the poor chimney sweep Tom who drowns and becomes a water baby, was called by Chesterton “a breezy and roaring freak; like a holiday at the seaside.(ii) One fantastic adventure follows another—a technique Carroll would later employ in Alice and MacDonald in The Princess and the Goblins—wherein Kingsley rails against the wretched plight of Victorian sweeps (considered the most oppressed, degraded, and tortured children in English society), includes cameos from nature (such as the activities of various insects), and preaches the possibility of redemption (even for a brute like Mr. Grimes). Other Victorian conventions are satirized as well, such as the Isle of the Tomtoddies, which takes a swipe at English education by describing the inhabitants as “all heads and no bodies,” who never learn anything because they spend all their time preparing for examinations.

“The harder a man fights against evil,” said Kingsley,“the harder evil will fight against him.” Kingsley fought against evil, even to the point of employing fantasy to right wrong.

Footnote:

(i) Roger Lancelyn Green, Andrew Lang: A Critical Biography with a Short-Title, 11.

(ii) G. K. Chesterton, The Victorian Age in Literature.

About the author:

Kenny Chumbley, a native of the Illinois prairie, is a minister, author, and publisher. He has authored one children’s story (Ol’ Pigtoes) and two fairy tales (The Green Children, the Literary Classics 2017 Enchanted Page Award recipient for best children’s storybook, and The Goblins Who Stole a Gravedigger, an adaptation of Charles Dickens’ first Christmas ghost story). He has also written and produced two musical plays based on his two fairy tales.