Book Review

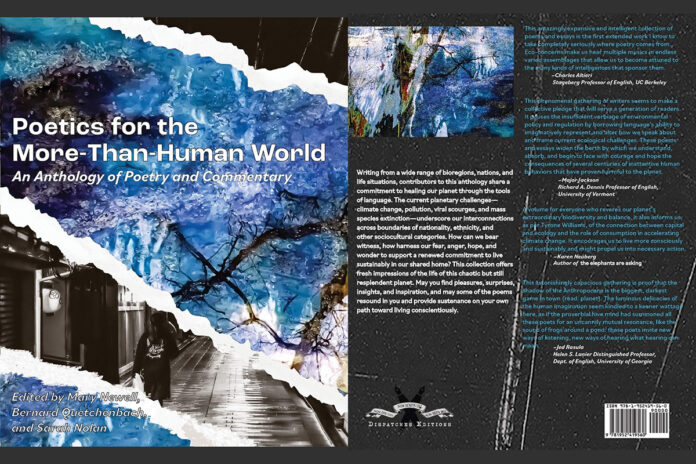

Poetics for the More-Than-Human World:

An Anthology of Poetry & Commentary

Edited by Mary Newell, Sarah Nolan, and Bernard Quetchenbach

*

For a hefty anthology of ecologically oriented poetry, this book has a strange dedication:

May some of these words leave footprints

for those who come after

Perhaps not the best choice of words: many readers might be conscious of carbon footprints when opening a book such as this one! However, let’s not be too punctilious here. We should be very glad indeed that such anthologies are being created. Or should we?

We are in the realm of ecopoetics in which the lyrical ‘I’ makes way for “a more communal perspective”, as Harriet Tarlo says. The avoidance of the ‘I’ is well-known in haiku literature, a genre not represented in this anthology, unfortunately, except in a renga by Brian Teare.

I must say I really very much like the idea of including essays in this anthology. There are things that can only be said in poetry, and things that can only be said in prose (though for many poets the borderline is often blurred –and I’m not talking about the prose poem, an underused genre if ever there was one). Having said that, I wondered would the essays indulge in one of the great pastimes of our age, namely, obfuscation.

The Introduction mentions Hinge theory. It rang a bell. A warning bell? I had to look it up. I found this:

‘Hinge is material of connectivity and introduces an intentional and generative biasing. Like a pool table with all the balls commotioning and someone lifting the pool table slightly so all that activity is directed. (With the additional image that new balls are being added all the time as the pool table itself enlarges).

Am I any wiser? I’m afraid not. I’d prefer a haiku, thank you. Preferably in Irish, or in some language that tries to make sense most of the time. The originator of the Hinge Theory is Heller Levinson and after reading his poems here I wondered, sadly: is the world worth saving?

Levinson has ‘seeping poems’ in this anthology. I checked the internet to see what could be found out about Levinson’s book Seep and this exploded nastily in my face:

Seep does just that. Averse to blockages, the automatic, the preconditioned, & the stale, like some noble behemoth long composing, long soaking in salubrious underworlds, prickling with the agitation of anointed vision, this tome releases: exploration of terms such as – ‘seepage, ‘ ‘brood, ‘ ’emptiness, ‘ ‘shadow;’ . . .

Sorry, could you repeat that? Might it be that poetry, not plastic, is choking our world? Indeed, could this be what the Introduction to the anthology is inadvertently stating when it opines as follows:

‘the present moment has, needless to say, become dangerously unstable, in large part because we humans have understood the voices we hear around us as less rather than more than human . . .’

When I flick forward to the essays section, Sharon Lattig writes.

‘This condition of potential connectedness, active while it is masked, must remain unseen since seeing, poetic and otherwise, determines, lopping off ramifying potential . . .’

Didn’t quite get that. Could you repeat, please? Come on! Who speaks like that? Nobody, of course, and yet today’s poets and academics seem to have a license to string words together in ways that are so far removed from the spoken word that they divorce themselves from the natural world and commonsensical rules of communication, something that hasn’t happened yet to many lesser-spoken languages – though you can be sure that many of them are trying their damnedest to ‘catch up’, as it were!

Juana Adcock has an alphabetical advantage over her peers in this anthology, as she will have in any other alphabetically-arranged anthology that features her work. Juana is described here as Mexican-born and Scotland-based who performs in Spanish and English. But that’s not the whole picture. I happen to know that Juana also performs in Scots, and sometimes in Greek and Italian. In fact, Poetry International Archives has a quote from Juana that is fascinating and very relevant to our discussion:

I recently wrote a long love poem to the Scots language … The poem moves between different languages, in this case English, Scots, Spanish and Italian. Whilst performing it I become hyper-aware of where the words sit in my body: I was already well familiar with the way Spanish booms in my chest while English thins out above my head, but I was amazed by how the Scots goes back down to my chest.”

Can we have ecopoetics without ecolinguistics? (I’ll say nothing about neurolinguistics, psycholinguistics, ethnolinguistics, etc.). Thank you, Juana, for a memorable quote: ‘English thins out above my head!’

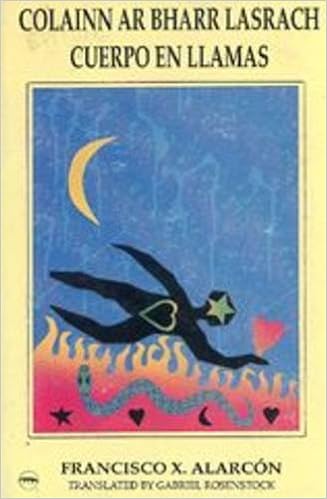

I frequently and lovingly recall the days I spent with the Chicano poet Francisco X. Alarcón (1954 -2016):

Before we began a reading from Cuerpo en Llamas, Francisco burned dried sage in a shell and invoked the spirits of his Aztec ancestors in a language I had never heard before, Nahuatl. We had come to address the students of Fr. Pádraig Ó Fiannachta, Professor of Old and Modern Irish in Maynooth University, not with an arid treatise on ecopoetics but with the fire and eloquence of ecopoetics as a living treasure, the key to our past and future.

If more US poets and professors – too often one and the same – embraced a pre-Columbian language, the face of ecopoetics in the US would change, utterly. In the beautifully named anthology from Norton, When the Light of the World was Subdued, Our Songs Came Through, more than 160 poets from almost 100 indigenous nations are represented. You won’t find them here. The exclusion from this anthology of such great American voices as N. Scott Momaday and Joy Harjo is inexplicable! Not even a mention. Of course, Momaday and Harjo write poetry that is universally understood, so it can’t be any good, can it?

https://emergencemagazine.org/story/language-keepers/#/chapter/introduction

Millions of Americans are unaware of the linguistic emergencies at their own doorstep.

Irish, the literary medium of my choice, is an endangered tongue and many dismiss it as a language of the past. How refreshing, therefore, that Michael Cronin in his seminal work Irish and Ecology (FÁS 2019) takes the opposite view, calling it one of the languages of the future. Cronin quotes Russ Rymer from National Geographic:

‘Small languages, more than large ones, provide keys to unlock the secrets of nature, because their speakers tend to live in proximity to the animals and plants around them, and their talk reflects the distinctions they observe. When small communities abandon their languages and switch to English or Spanish, there is a massive disruption in the transfer of traditional knowledge across generations . . . about medicinal plants, food cultivation, irrigation techniques, navigation systems, seasonal calendars.’

The well-named Rymer speaks plainly and makes more sense than a lot of the poets and academics garnered in this volume.

There are poets here with Irish names who are not well known in their ancestral homeland, such as Peter O’Leary, described here as ‘the most audacious American poet alive.’ O’Leary – unlike the Irish writer of the same name, Peadar Ó Laoghaire – makes room for mushrooms and if you haven’t come across him yet, you are encouraged to ‘read, re-read, ponder, live with and marvel at O’Leary’s dazzling, dark, and profoundly strange and wonderful reimagining of our fungal and linguistic world.’

It’s not the definitive acid test for good poetry, but if I can translate a poem into Irish, that poem then becomes meaningful for me and I blog the translation (or transcreation). Opening this anthology at random, I attempted to translate a sonnet by Cynthia Hogue:

Not heard but seen Dun/ done

The not-song of the no “song pervade his Lips”

I gave up! I think it was the italicized ‘p’ in ‘pervade’ that brought me close to a nervous breakdown. OK, I say to myself. Don’t give up. Try again. Fine, here goes. What’s this, then?

after sword laden days quiet

sweat worne hands touch wrapt

What have we got here? It turns out that the poet, E. J. McAdams, has taken five-letter words from a work by Sir Thomas Browne. Good luck to both of them, I say! I think I’ll gather some four-lettered words from the collected poems of McAdams. Wouldn’t that be fun? Chop-chop-chop! The art of vivisection.

I greatly miss writers from the Celtic languages in this anthology. They would never italicize a ‘p’ or create a poem from three-lettered words found in The Táin, let us say. (Though you never know what to expect these days.)

Fine translations of Nuala Ní Dhomhnaill and Cathal Ó Searcaigh exist, to name but two Irish-language poets who are close to the spirit of ecopoetics. (Other poets such as Biddy Jenkinson are not widely translated into English: for some, it is their express wish not to be ‘Englished’). Of course, English dilutes the universe terribly and, indeed, not everything can be expressed adequately in English. Let’s face it, some poems cannot be translated (or transcreated) into English at all, especially poems of a shamanic thrust.

I found this out myself when I read a few poems, bilingually, for a University archive. One of the poems could not step over a huge abyss into an English-language casing. It would have suffocated. In fact, it would have sounded trite, or ridiculous, possibly even unhinged. For the record, this is the untranslatable recitation:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IIe__p81E8k

As I sat, uncomfortably, in the antiseptic groves of Academe – not a fish, or a flower, or a worm to be seen –chanting a shamanic poem, I couldn’t help thinking how everything in society, from cradle to grave, conspires against ‘this kind of thing!’

I may be a simple-minded, simple-hearted being but I have to admit that much of the material gathered in this anthology is too much for me. I don’t know if it is bombast, gobbledygook, mystification, mumbo jumbo, flimflam, or a combination of all the above but it has me frazzled.

The academic has a scientific tendency to cut things up and analyse the various parts; a lot of the poetry in this weighty volume looks like it has been chopped up by the poet, for analysis, rather than emanating as a song from the diaphragm and throat. (I better not mention the soul here as it would be unscientific).

* * * *

OK, we began with Adcock. Who’s next for shaving? (Will I ever reach B at this rate?) Alphabetically, it must be Will Alexander who says, ‘So as to accelerate quasi-neural lightning that levels other than psychic astigmatism and its related detritus engages collective telepathy . . .’ Sorry, could you repeat that? We are informed that Will has been translated into Romanian, Italian, Spanish, Cyrillic – Cyrillic is a language? –and Arabic. I’m looking forward to the English translation (though I fear it may go over my head).

Book Publication Details:

Paperback: 546 pages

ISBN-10: 1952419565

ISBN-13: 978-1952419560

Dimensions: 19.05 x 3.48 x 23.5 cm

Publisher: Spuyten Duyvil Publishing (12 Nov. 2020)

About the Reviewer/Author

Gabriel Rosenstock is a bilingual poet (in Irish & English), haikuist, tankaist, playwright, novelist, short story writer, essayist, translator, writer for children and champion of ‘forlorn causes’ – the phrase is Hugh MacDiarmid’s. He is a Lineage Holder of Celtic Buddhism and a member of Aosdána (the Irish academy of arts and letters). Among his awards is the Tamgha-i-Khidmat medal (Pakistan) for services to literature. Gabriel’s most recent volume of poetry is Glengower: Poems for No One in Irish and English (The Onslaught Press). His website: https://www.rosenstockandrosenstock.com