How does literature respond to death or A Near-Death Experience?

By Mitali Chakravarty

Be silent in that solitude,

Which is not loneliness—for then

The spirits of the dead who stood

In life before thee are again

In death around thee – and their will

Shall overshadow thee: be still.

(From Spirits of the Dead by Edgar Allan Poe, 1827)

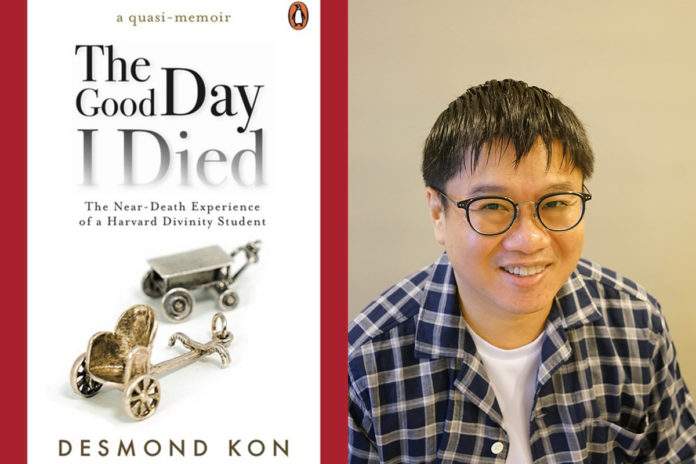

Almost two centuries ago, Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849) wrote these lines. Why did he write these lines? Why did he write of spirits? Did he glimpse life after death as described by the well-known Singaporean poet and writer Desmond Kon Zhicheng-Mingdé in his recent book, The Good Day I died, The Near-Death Experience of a Harvard Divinity Student (2019)?

Desmond in his ‘quasi-memoir’ (as he calls his narrative) tells us of his near-death experience in Harvard where his heart had stopped beating and he had to be resuscitated.

“There were thousands of people, all lit like white light, walking in one direction. Down the road, making a right turn, and out into the main road. Again, this only reflected the route outside my house, yet there were none of the accouterments. I remember being in awe of the sight, but I never joined them. I was always behind the window.”

And Desmond remained in the room till he was returned to his body – in effect asked to go back as he was not ready to die. He had a telepathic conversation with angels who “told him to return if that was what I wanted. They then said: ‘We’ll come back for you another time.’”

Desmond goes into the circumstances, touches on them but not quite – his post-structuralist book is more an intellectual, erudite discussion with outbursts of emotion that touches the heart with poetic intensity. His choice of words essentially defines his experience – for instance, the use of the word “accouterments” gives a sense of a ceremonial procession almost Catholic in its intent. Desmond confesses he attempts a spiritually-centred worldview and lifestyle with his Christian upbringing, from a spiritually inclined family as he tells us in his book and has studied world religions in Harvard. He admits, “Were they angels? I would like to say there were. But to be responsible to both the reader and my memory, I’ll freely admit that I use the word ‘angel’ because that is the language I choose to access.”

But interspersed with his telling are literary outpourings from 2007 till now that he brings in to bridge the gap between our comprehension of the enormity of what he experienced and how it impacted his future life – for one he changed the flow of his career from that of a journalist to that of a full-fledged writer doing things that were more meaningful to him. “As mentioned previously, my own poetic vision and style started attaining a greater transparency.”

He has used some of his own earlier published works and interviews to summon more empathy for his experience.He has brought in his extensive research for this book and quoted many writers and books through his telling. While most writers would write the story, he meanders in a post-structuralist fashion. We pick it up in bits as we read. There are chapters on the real experience interspersed with his observations on the impact it had on his own work and reading. What makes this book unique is partly the post-structuralist telling. The other unusual feature in the book is it runs like a self-administered interview.For instance, he has a chapter heading – ‘Recollection’ followed by a question like “Many NDE accounts share surprisingly similar details. Let’s go through systematically the various elements of NDEs. Did you have an out of the body experience? Was there, for you, a distinct separation of your consciousness from your material body?” And he goes on to answer the question in this Chapter, starting: “Definitely, I had an out-of the body experience…”The next chapter is Disclosure, where he brings in his experience of angels. To authenticate it, he brings in interviews he has had earlier on his experience in journals. And then he plunges into his poetry and his work and the Bible. He quotes – sometimes, from the deconstruction of Jacques Derrida (1930-2004) and multiple post-structuralist writers, sometimes the Bible, sometimes his own works and sometimes, more conventional structured writers. His post-structural creation knows no bounds of erudition or of deconstruction

At the end of the book he talks of his takeaway, his insights – another feature that make the book really unique. He has devoted a whole chapter to this and come up with values that should move mankind: “Humility. Kindness. Gratitude.” and “Love is the answer.” He has gone into different lores to find answers. He quotes from Thich Nhat Hanh’s book How to Love:“True love is made of four elements: loving kindness, compassion, joy and equanimity. In Sanskrit, these are maitri, karuna, mudita, and upeksha. If your love contains these elements, it will be healing and transforming, and it will have the elements of holiness in it.”

He even pauses a moment to glimpse at Emily Dickinson’s dignified stance- “Because I could not stop for death / He kindly stopped for me” in her poem The Chariot(1890). He wonders if he should have gone with the angels, but he does not “have definitive answers”, he admits. However, he concludes his book with ecstasy in having lived on –“Wonderful, even as so much remains to be known, the world filling itself with wonder. Wonderful. Wonderful indeed.”

And does anybody have a definitive answer?

In A Heart of Darkness (1899), Joseph Conrad tried to trace the death experience of the villainous Kurtz: “Anything approaching the change that came over his features I have never seen before and hope never to see again. Oh, I wasn’t touched. I was fascinated. It was as though a veil had been rent. I saw on that ivory face the expression of sombre pride, of ruthless power, of craven terror – of an intense and hopeless despair. Did he live his life again in every detail of desire, temptation, and surrender during that supreme moment of complete knowledge? He cried in a whisper at some image, at some vision – he cried out twice, a cry that was no more than a breath:

The horror! The horror!”

And Kurtz died.

In antithesis, Desmond returns to life to enjoy the wonders of living – to discover that life is a gift and the best thing that he can have. Earlier in his NDE, he does talk of going through a few moments of terror before he emerges out into the white light experience. He writes, “Yes, the sense of fear was terrifying. The sheer intensity” and“I felt myself drowning, choking on something red-hot as that had the taste of blood and rust and fire, as if I was drowning in lava.”

Desmond takes refuge in his studies and intellectual explorations to seek answers for what he experienced – in books, in poetry, in the world around him. And he emerges a living, throbbing individual researching NDE with a book that has been called “expertly written, very easy to read, and enthusiastically recommended” by Jeffrey Long, MD, a New York Time bestselling author and the founder of NDE research foundation. The book has been hailed by Poet and Director of Poetry Festival Singapore, Eric Tinsay Valles (with who now Desmond is bringing out another anthology of poems) as “a poststructuralist confession, an exegetical survey of Desmond Kon’s oeuvre”.

The book also gives us glimpses of writing with a purpose, of lyricism and spontaneity which certain schools of literature frown on.The author does not halt to follow a single structured narrative, which is as wide as the range of his reading and imbibing. He has drawn from Khalil Gibran (1883-1931) as much as he has from Poe and Jean- Jacques Rosseau (1712-1778). His prologue starts with a quote from Rousseau – “Absolute silence leads to sadness. It is the image of death.” At the bottom of the page is a quote from Gibran: “For Life and Death are one, even as the river and the sea are one.”

Perhaps as Desmond’s book deals with living and dying only – unlike other books where dying is part of the story, the narrative transcends the binds and bonds of literary schools and thoughts. It soars a la post-structuralist mode to address the basic wonder of living and dwells on the miracle called life and death, an appreciation of the fecundity, the beauty of this life and the Earth. These lines from Omar Khayyam’s Rubaiyat perhaps best capture the spirit of his book, which continues fascinating in its execution of exploring the basics of existence – living and dying and coming back from death – a journey undertaken by Nachiketa with intent but by Desmond by accident.

Ah, make the most of what we yet may spend,

Before we too into the Dust Descend;

Dust into Dust, and under Dust, to lie,

Sans Wine, sans Song, sans Singer and–sans End!

(From Rubaiyat by Omar Khayyam (1048-1131), translated by Edward Fitzgerald (1859))

About the Reviewer

Mitali Chakravarty’s poetry has been published online and as part of anthologies. Her works have been translated into German and her poetry has been part of a recent PEN symposium. She has published a humorous book of essays on living in China where she spent eight years, In the Land of Dragons (2014). In April 2019, she joined kitaab.org as the editor. She blogs at 432m.wordpress.com.